You have a Surname DNA Project at FamilyTreeDNA. You have grouped your project members into a variety of genetic groups, based on the principle that, in any given group, the members appear to be related since the emergence of surnames (roughly 1000 AD in Ireland and 1200 AD in England). So how do you go about analysing each group and reporting your findings to your project members?

Here is the approach that I use with my various surname projects. My focus is on Irish surnames specifically, but this process can be adapted for surnames of any country. What I describe below is only one way of approaching the question, and other project administrators will have different approaches or variations on the one below, but hopefully this article will give you an idea of how you could approach the topic of analysing each genetic group within your project. Feel free to take what you like, adapt it for your own particular circumstances, and leave the rest. And if you have a better way of doing something, leave a short description in the Comments section below - I'm always on the lookout for hints, tips & shortcuts.

Before you start ... lay the foundations

Prior to starting the project, it is worthwhile exploring three different aspects of the surname (and writing up your findings as a blog post or article for your project members to read - I use Google Blogger because it is free and relatively easy to use). Here are the three topics:

1) Surname Distribution Maps - these give you a good idea of where the surname is particularly concentrated within the world. And you can look out for these locations among the EKAs (Earliest Known Ancestors) of your project members. For Irish surnames, maps based on Griffiths Valuation (mid-1800s) are available via John Grenham's website (subscription) and Shane Wilson's website (free). Barry Griffin's website (free) offers maps based on the 1901 & 1911 censuses. Here are some useful links, but you could also ask ChatGPT (or other AI engines) for more information or for Maps of non-English surnames:

- John Grenham's website (Irish Ancestors) ... https://www.johngrenham.com/

- Shane Wilson's website (Wilson.info) ... https://www.swilson.info/sdist.php

- Barry Griffin's website (Irish Surname Maps) ... https://www.barrygriffin.com/

- Forbears website (useful for world & continental maps) ... https://forebears.io/surnames

- Public Profiler - GB names (British; recently revamped) ... https://apps.cdrc.ac.uk/gbnames/

- Public Profiler - World Names (Global; currently not working) ... https://apps.cdrc.ac.uk/worldnames/

- Archer's DNA Atlas (British; available on CD) ... http://www.archersoftware.co.uk/satlas01.htm

2) Surname History - various surname dictionaries exist and these can give a useful account of where a particular surname arose, what type of surname it is (e.g. patronymic, locative, occupational, etc), if it has a particular meaning, if it is single origin or multi-origin, and what other surnames may be associated with it. This information has implications for your DNA Project because it may give you clues as to how many genetic groups to expect, which of them are likely to be the largest, and where the ancestors of group members are likely to come from.

Useful surname dictionaries include the following:

- Woulfe's surname dictionary (Irish Names & Surnames): a useful searchable digital version is available on the Library Ireland website and the original 1922 edition is on Archive.org.

- McLysaght's surname dictionary spans several discreet books but none of these are available online and all are currently out of print. They can be found in libraries and second-hand bookstores (but I find Woulfe's dictionary more informative):

- The Surnames of Ireland. 1957

- Irish Families. Their Names, Arms and Origins. 1957

- More Irish Families. 1970

- the "Irish Names" section of John Grenham's website (Irish Ancestors) is also helpful.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland is currently available for free as a Kindle edition from Amazon.

You can read some useful examples below of how surname dictionaries can help set the expectations for your surname project:

- the Ryan name in surname dictionaries

- the Gleeson name in surname dictionaries

- the Farrell name in surname dictionaries

- Bart Jaski's genealogical tables (available as a 72-page pdf document)

- the Ó'Cléirigh Book of Genealogies by Cú Choigcríche Ó Cléirigh (O'Clery). A pdf version is available to view on JSTOR here and can be downloaded if you have an account. See also this Wikipedia article here.

- the Great Book of Genealogies (Leabhar Mór na nGenealach) was edited from the original (1649-1650) and published in 2004. It comes in 5 heavy volumes and costs about 600 euro. It has not been digitised and is not available online, so you would probably need to consult it at a specialist library. The original manuscript (in Irish) is available online here. See also this Wikipedia article for further information.

- a list of key manuscripts containing Irish medieval genealogies can be found on this Wikipedia page here - some have links to online versions. And another Wikipedia page contains a list of medieval Irish manuscripts that may be relevant to your research.

- if you are researching a particular surname, ask ChatGPT what manuscripts it would recommend consulting.

Key question to address in your analysis of each group ...

When we come to analysing each group in turn, my starting point is a series of seven questions:

- What is the dominant surname variant in the group?

- How old is the group? How long have they been carrying the surname?

- What are the chances of a Surname / DNA Switch (SDS; a.k.a. NPE, Non-Paternal Event)?

- Is there any evidence of an SDS / NPE?

- Where is the group from?

- What is the branching structure within the group?

- Can we connect the group to the Irish medieval genealogies?

Let's address each question in turn.

1. What is the dominant surname variant in the group?

This is important because some surname variants can be localised to a specific area. And this can signpost project members to a particular set of records. Some examples are given below (summarised by ChatGPT ... and thus to be taken with a pinch of salt, but you get the idea).

2. How old is the group? How long have they been carrying the surname?

In order to calculate this, at least two people with the relevant surname need to have tested. If they have both done the Big Y test, then they will appear on the Time Tree, and will have a TMRCA estimate (Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor) via the "Scientific Details" tab on the Discover feature. This age estimate tells you roughly how long the name has been carried by the ancestors of the two members of this group.

There are several caveats to be aware of.

- These age estimates come with very large Confidence Intervals, usually several hundred years. In other words there is a large range, and even with lots of data, these ranges will never fall below +/-50 years. So the estimates will never be more precise than a one hundred year period. Let's take the 95% Confidence Interval for FT86146 as an example - 1238 CE (95% CI 1036-1402). This range stretches from -202 years to +164 years, a span of 366 years.

- The estimates will evolve over time as more Big Y data becomes available. For example, the TMRCA for BY35730 changed from 1029 AD (Jun 2022), to 885 AD (Aug 2022), then 802 AD (Sep 2022) and is currently 711 AD (Jul 25). So the central estimate has decreased by 318 years since mid-2022.

The Take Home Message is: do not put a lot of faith in the central estimate - it will change over time, sometimes by several hundred years. And therefore be very wary about assigning a particular SNP marker to a specific named ancestor in the genealogies (medieval or modern) just because their year of birth is close to the central estimate.

In the example above, I had to say something along the following lines to the members of Group 3a in the O'Malley DNA Project:

"The overarching DNA marker for this group was BY35730. The term overarching was thought to be appropriate because it encompassed all O'Malley men in the group. However, it now has a (current) age estimate of 711 AD (with a large range of 362-993). The central estimate (711 AD) has now moved outside of the Surname Emergence Era in Ireland (roughly 950-1150 AD) so we now need to consider if it would be more appropriate to identify a downstream DNA marker as being a more likely candidate for the overarching DNA marker for this group. And that now leaves one O'Malley man outside of the group. It may very well be that his O'Malley surname arose independently of everyone else in Group 3a."

You can read more about this example here.

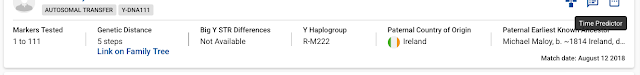

In the absence of at least two Big Y tests, you will have to rely on TMRCA estimates calculated solely on the basis of STR marker data. These can be hugely misleading, especially when there is a lot of Convergence present, and thus should be taken with a huge pinch of salt. These estimates can be accessed by using the Time Predictor tool (the last icon at the end of the row of the relevant match).

3. What are the chances of a Surname / DNA Switch (SDS / NPE)?

Given that the average rate of an SDS / NPE is 1-2% per generation, then the chances that such an event occurred on a direct-male-line over the period of the last 1000 years is 33-55%, calculated thus:

- let's assume 25 years per generation, so in 1000 years (i.e. 1000 AD to 2000 AD) there are 1000/25 = 40 generations

- the probability of having no SDS / NPE in 40 generations at a 1% incidence rate is 0.99^40 (i.e. 0.99 multiplied by itself 40 times) = 0.669 (i.e. 66.9%) ... and therefore the probability of having at least one SDS / NPE is 1 - 0.669 = 0.331 (33.1%)

- with a 2% incidence rate, the calculation is 1- (0.98^40) = 1 - 0.446 = 0.554 (55.4%)

- and thus the overall incidence rate is about 33% - 55% over the 40 generations

If instead we use 30 years per generation, then the rate is about 28% to 49%.

So (for ease of explaining to others), I usually round the overall estimate to 50% and tell people that everyone has a 50:50 chance of an SDS / NPE on their direct male line over the last 1000 years.

So if the TMRCA estimate is 1650 (as in the example above), then this leaves 650 years unaccounted for (i.e. 1000 AD to 1650), which is 26 generations (@25yrs per gen), then the probability calculation is 1 - (0.99^26)% to 1 - (0.98^26)% = 23.10% to 41.26%

Or you can simply ask ChatGPT: what is the risk of an NPE on the direct-male-line assuming the following - an NPE rate of 1-2%, a time period of 650 years, and 25-33 years per generation?

In the example, it is useful for project members to know that the chance of an SDS / NPE between 1000 AD and 1650 AD is in the range of 23-41%. This braces them for the distinct possibility that the surname on their direct-male-line may have been a different surname to that which they carry today, but the switch probably happened some time before 1650.

I discuss the various potential reasons for a switch in two articles, one dealing with more modern causes and the other with more medieval causes.

4. Is there any evidence of an SDS / NPE?

Various pieces of evidence point to the likelihood that an SDS / NPE has taken place on a project member's direct-male-line.

1) the project member is already aware of it and has given you all the relevant details.

2) the project member has supplied information about their EKA (Earliest Known Ancestor) and the EKA has a different surname to the project member.

3) the participant does not match any known test-takers with the surname of your surname project.

4) none (or few) of his STR matches have his surname. In fact, some other surname may predominate.

5) the project member has been placed on the Time Tree but is surrounded by people on adjacent branches who all have the same surname, but it is not his. See the MacPherson / O'Malley example below and here (from the Group Time Tree for the M222 Project).

If you can think of any other indicators, please leave a comment in the Comments section below.

5. Where is the group from?

This is a really important question to answer for the individual project member as it may signpost him/her to a specific record set for further documentary research.

Ideally it would be great if each project member supplied their EKAs birth location, including country, county, and town / townland. In time we might be able to associate people from a particular town or townland with a specific DNA marker.

Assessment of the surname in Surname Dictionaries and Surname Distribution Maps will have given you some idea of where to expect some genetic groups to come from. Evidence for a group's likely ancestral origins can be assembled by several different methods.

1) some people include ancestral location with their Earliest Known Ancestor details (Account Settings > Genealogy > Earliest Known Ancestors > Direct Paternal Ancestor). This is displayed on the public Results Pages of any projects to which they belong, and on the Group Time Tree, and on their Profile if they appear on the list of matches of your project members. But many people only have their EKA name, and sometimes birth & death dates. And only 50 characters are allowed in the Direct Paternal Ancestor field, which may not be enough to include birth location.

2) alternatively, some people have included their EKA birth location in the Paternal Ancestral Location field (Account Settings > Genealogy > Earliest Known Ancestors > Paternal Ancestral Location). But this is NOT displayed on project Results Pages or the Group Time Tree. To access this data, Admins can log in to their GAP pages, go to Reports > Member Reports > Paternal Ancestry, sort the members by "Sub Group", and scroll down to the relevant group. This is what the information looks like ...

You can see from the above that information about EKA birth location is sometimes not entered at all, sometimes in one field, sometimes in the other field, and sometimes in both. And thus sometimes the data is visible on the public Results Page (data from the Direct Paternal Ancestor field) and sometimes it is not (data from the Paternal Ancestral Location field).

Admins should also be aware that the titles of the columns above and the fields from where the data is obtained are not exactly the same i.e. the Direct Paternal Ancestor field feeds into the Paternal Ancestor Name column, and the Paternal Ancestral Location field feeds into the Map Location column.

Lastly, this particular approach only works for people who are in your project. You cannot get this information for people who are outside of your project because you do not have access to their data.

Admins should encourage project members to enter EKA birth location information because many testers will not realise the importance of doing so. Admins can help their project members do this by emailing them and providing instructions on how to do so (include a link to this explanatory article if you like). I would suggest to recommend putting the EKA birth location in the Direct Paternal Ancestor field (which will allow it to be made public on the Results Page) and forget about the Paternal Ancestral Location field (which is not made public on the Results Page).

Alternatively, if you have their permission to do so, you can update this information yourself (but they will need to give you Advanced Access first by logging in to their account and going to Account Settings > Project Preferences > Group Project Administrator Access, then find the relevant project, click the pen icon on the far right of the row to edit the preferences, then scroll down through the text of the pop-up box to find the relevant Admin name, then in the Access column click on the drop-down menu and select Advanced).

3) email people and ask them for their EKA's birth location.

4) for members who have not displayed their EKA birth location, or simply don't know, you can look at the birth locations of their closest genetic neighbours. This can narrow down their likely ancestral origin to a country and even a county.

If the test-taker has done the Big Y test, a first step would be to go to FTDNA's Discover page, enter their haplogroup, click on Time Tree, and assess the country flags that appear on the tester's branch and adjacent branches. You could also click on Country Frequency, and then Table View. This brings up a list of countries (and associated flags) and the number of tested descendants per country. Predominant numbers stand out and indicate the likely country of origin.

The country flag is determined by the information the test-taker has entered in the Country of Origin field (at Account Settings > Genealogy > Earliest Known Ancestors > Direct Paternal Ancestor). Martin McDowell has made a helpful video about how to use and interpret this information here. One of the points that Martin makes in this video is using the Country Frequency "Table view" to determine the country of origin information for any specific haplogroup. This gives a very clear view of how many people have entered the info, and how many haven't (i.e "Unknown Origin" entries).

You can also use the Ancestral Origins table (on the project member's Homepage, go to Results & Tools > Y-DNA > Ancestral Origins). Another option is the Matches Map feature on FTDNA (on the project member's Homepage, go to Results & Tools > Y-DNA > Matches Map, and select marker level in the top left). The latter two options have to be done member by member via their Homepage (potentially a time-intensive task), but can provide useful information that suggests a likely county of origin (as in the example below).

6. What is the branching structure within the group?

Defining the branching structure essentially creates a genetic family tree for the group. Any available genealogical data can be hung onto the branches like baubles on a Christmas tree. In effect, DNA markers become substitutes for ancestors when the genealogies run out (i.e. hit a Brick Wall ... which is typically around 1800 for Irish research).

This also emphasises the importance of trying to recruit people with extensive pedigrees to your project - determining their DNA branch will allow others to see if they too sit on the same branch and can therefore "piggyback" onto the known genealogy.

A good example of this is the Royal Stewart project where it is estimated that over 80,000 people have benefitted from the Big Y tests of 4 specific members with extensive lineages.

There are several versions of the Y-Haplotree that help to illustrate the branching structure for a genetic group, but none of them are optimal. Here are the key differences:

- Time Tree - this displays Big Y data only. It displays country of origin, but there are no surnames of test-takers, or EKA details. The big advantage of the Time Tree is that it displays all the known branches determined by Big Y testing.

- Group Time Tree - this displays branches with both 1) test-taker surnames & 2) their EKA details. But not all known branches are displayed because a) test-takers have not reset their default display settings, or b) wish to remain private, so only a partial view of the Y-Haplotree is presented.

- Classic Tree - this has all the branches, country of origin, rounded dates for TMRCA estimates, & SNPs per block ... but no test-taker surnames or EKAs.

- Big Y Block Tree - this is not public and can only be seen by the test-taker or project Admin. It includes the full names of all matches, and their EKAs can be obtained by clicking on their name (twice). This also reveals the number of SNPs per SNP block and their names.

- Public Y-Haplotree - this contains data from SNP Packs and single SNP tests as well as Big Y data. As a result, this has a bottleneck effect in that people who have only done SNP Packs or single SNPs will end up in big clusters on upstream branches. This can be misleading if you don't know what's going on, because it looks like some surnames "belong" on upstream branches whereas if the people had done Big Y testing instead of a SNP Pack, then they would have been moved to a more relevant sub-branch downstream. This tree can be accessed a) at the bottom of the FTDNA homepage under "Community", b) via the GAP pages (Reports > Genetic Reports > Y-Haplotree) and c) here. This tree can display test-taker surnames (switch to "View by: surnames") but only in a very limited way - this only happens if at least 2 people on a branch have exactly the same surname spelling.

- test-taker surnames & EKA details, including birth location - these can be gleaned from several sources:

- your project's public Results Page

- your Group Time Tree

- the Big Y Block Tree (be aware that some of these will have their display options set to private and thus the diagram you are creating should only be used for analysis purposes)

- the match lists of your project members who sit on the branches associated with this group (again, some of these will have their display options set to private)

- a Google search for the SNP that characterises each branch or sub-branch (i.e. google: "FTDNA" and "SNP name" and "-Discover")

- TMRCA central estimates - obtained for each SNP from the Scientific Details tab on the Discover feature

- number of SNPs in each SNP block - obtained from the Block Tree or the Public Y-Haplotree. Knowing this gives you some idea of the chances that further Big Y results might cause a split in any given SNP-block.

- relevant STR matches - these can be added manually to the diagram if there is clear evidence of a USP (Unique STR Pattern) that is likely to be predictive of a particular SNP-defined branch.

7. Can we connect the group to the Irish medieval genealogies?

The Irish medieval genealogies are the oldest in Europe. They extend back in time to the dawn of surnames (1000 AD or thereabouts), and before that to the advent of literacy in Ireland (600 AD or thereabouts), and before that into the semi-mythological past.

However, there is a large gap between most Irish Brick Walls (around 1800) and the time when most medieval genealogies run out (about 1600, or beforehand). So one challenge is to bridge that 200+ year gap between 1600 and 1800.

Another challenge is to figure out which genealogies are accurate and which contain errors, or have been deliberately fabricated for sociopolitical gain.

DNA can help tackle these challenges and there are many instances where the DNA has either confirmed or refuted the veracity of the genealogies. For example, the O'Malley clan of Mayo do not connect genetically where one would predict them to connect based on the genealogies, so there is probably a longstanding error in the genealogies.

Trying to connect a particular genetic group to the ancient genealogies involves a painstaking process that calls upon a lot of data, much of it outside of your own surname project. It involves firstly building a CAST (Clan-Associated Surnames Tree) based on the medieval genealogies, and secondly a DAST (DNA-associated Surnames Tree) based on the Y-DNA data. The two trees are then compared (CAST vs DAST) to look for consistencies and inconsistencies. Consistencies lend support to the relevant portion of the genealogies, inconsistencies highlight likely errors in the genealogies. A description of the process can be found in two FTDNA blog articles, starting here.

If you have any comments or suggestions, please leave them in the Comments section below.

My thanks to Martin McDowell and John Cleary for some suggestions and refinements to this article.